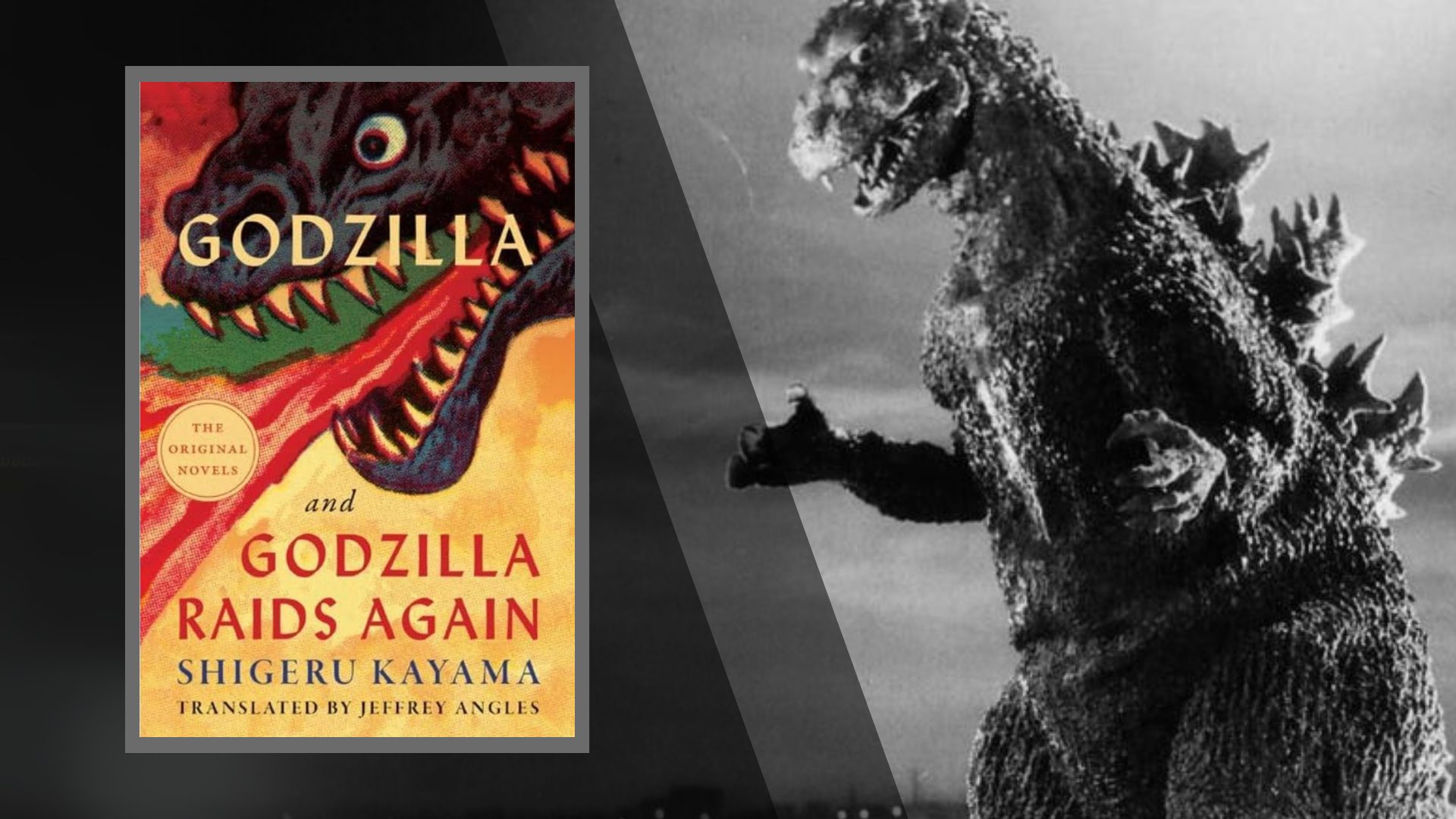

Somewhere on the list of what many of us are grateful for, no doubt, is Godzilla, celebrating his 70th Anniversary this year. But to celebrate the rampaging reptile’s nativity in a manner more befitting a septuagenarian, you might consider, instead of watching a movie, curling up with a cup of hot chocolate and a good Godzilla book.

Writers and directors, especially of genre fiction, sometimes dismiss allegorical readings of their work, no matter how obvious they may seem to critics and fans. No, no, they insist, we were just trying to tell an exciting story; there’s no way that we intended the giant monster shaped like a hammer and sickle as an allegory for Communism, or the alien with the huge rigid horn chasing the woman as a phallic symbol.

Shigeru Kayama (1904-1975) suffered from no such coy self-deprecation. The Japanese sci-fi and mystery author, who was commissioned to write the scenario for Gojira (1954) and its first sequel, originally released in the U.S. as Gigantis, The Fire Monster (1955) but now known in English as Godzilla Raids Again, freely admits that his now-immortal creation absolutely was intended as a symbol of nuclear devastation for a nation that had, less than a decade earlier, suffered it first-hand.

He says this in the foreword to a two-part book for young readers, a novelization of his stories for the first two Godzilla flicks, published in Japan in 1955. Godzilla, he observes, “doesn’t actually exist anywhere here on the planet.” He notes, however, that “atomic and hydrogen bombs, which have taken on the form of Godzilla in this story, do exist” and that his book is intended as a small salvo in the opposition to them.

We think of Godzilla as a cinematic icon, but it turns out that the beast was also the title character of a serialized radio play that was broadcast before the first movie was released, and also of many novels and countless comic books in the decades since, both in Japan and the U.S. But few of these works can claim the authenticity of this volume, translated into English by Jeffery Angles, a professor of Japanese at Western Michigan University, and published in a handsome paperback edition by University of Minnesota Press in 2023.

For Godzilla completists, it’s an obvious must. But this quick read is potentially fascinating for anybody, not only as a new angle (for Westerners) on the early days of a pop culture legend, but as a taste of Japanese popular literature, and also, as with last year’s superb Godzilla Minus One, on that nation’s postwar psychology.

Kayama’s style, at least as rendered in English by Angles, has an earnest, even naïve tone and a tendency to shift locales and points of view abruptly. He doesn’t go in for a lot of descriptive detail; for instance, our first look at the Big G himself goes thusly: “Suddenly, Godzilla’s head appeared from behind the ridge of hills before them. It was unimaginably enormous. It floated up in the darkness, emitting a pale white light as if painted with fluorescent paint. What a terrifying face! In his mouth was a cow, red with dripping blood.”

There’s also the matter of the sound effects which pepper the prose to an almost risible degree at times. On one page, we get the Don Martin-worthy “Fweet! Fwee-fweet!” (a train whistle), “Squeeeeeeech!” (the train’s brakes) “Kaboom! Crash, crunch!” (Godzilla attacking the train) and then the monster’s roar: “GRAAWRR!” This last rang a little off to me; the best phonetic rendering I ever heard of Godzilla’s unforgettable irritable honk was in a comic book pitting the beast against NBA great Charles Barkley: “KRRRREEEEEEONNK!” In his afterword, Angles explains that he actually toned this technique down from the original, as Japanese is far richer than English in onomatopoeia.

These stories also employ a few ideas that aren’t in the films. One of the most intriguing is the appearance of the “Tokyo Godzilla Society,” who send taunting messages to Godzilla’s enemies like this: “…If you hate Godzilla for killing your brother and you want Godzilla to die too, then you’ll likely befall the same fate as your brother…Our leader, the Great Lord Godzilla, will probably be back tomorrow night to stir up the weak-kneed, cowardly people of our nation.”

Even more intriguing is Kayama’s willingness, similar to that of Godzilla Minus One, to criticize his own country’s culpability for its wartime suffering. This comes out most frankly when one of the scientists, making the case for preserving Godzilla alive for study, remarks: “We Japanese have caused a great deal of trouble to people throughout the world. Carrying out this research is our one and only chance to make reparations for all that.”

This book is peculiar not only in the eccentricity of Kayama’s stories but in the extensive supporting material by the translator, a lengthy afterword and detailed, helpful glossary. His own prose seems unsteady and careless at times: “In an essay published in December 1955, a half year after the film came out in theaters, Kayama published an essay…” But his knowledge of his subject and the seriousness with which he takes it are admirable.

Angles notes that Kayama swore off writing any more Godzilla scenarios after he realized that Godzilla was becoming a beloved figure rather than an embodiment of a terrifying, world-threatening new technology. “In his eyes,” writes Angles, “allowing the monster to live represented a tacit approval of the hydrogen bomb.” Kayama also admitted that he was becoming fond of his monster himself. No doubt he would be annoyed to know that I, and millions of others, share that fondness.